Here you can read Rolando's latest interview with the "Times online" magazine. The interview was made because Rolando will stay on stage for 7 performances of "Les contes d'Hoffmann" (The Tales of Hoffmann) from 25th november till 13th december at the ROH.

Here you can read Rolando's latest interview with the "Times online" magazine. The interview was made because Rolando will stay on stage for 7 performances of "Les contes d'Hoffmann" (The Tales of Hoffmann) from 25th november till 13th december at the ROH.I think it's a very good interview, hope you enjoy it, too =)

Four years ago a hurricane blew on to the stage of the Royal Opera House. The opera was Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann, the staging a creaky production still best known for its association with Plácido Domingo, who had sung the title role when it was new in 1980. But now it finally had a star worthy to succeed him, a dishevelled figure who stumbled down the stairs on his first stage entry in a frighteningly convincing display of inebriation, and proceeded to thrill us all evening with his reckless charisma.

His name was Rolando Villazón, a Mexican tenor, like Domingo, and possessed, like Domingo, of a darkly baritonal voice wedded to a magnetic stage presence. Suddenly we had a fitting vehicle for the demonic, pathetic, obsessive role of Hoffmann, the poet who can’t separate his Gothic fantasies from his own hopeless life.

Villazón’s performance, his Covent Garden debut, catapulted him into the stratosphere. “It’s one of the most beautiful memories of my career,” he says. I was there, too, and perhaps the most endearing sight was Villazón jumping up and down with excitement as he received his ovation.

Villazón still wears his heart on his sleeve. I think my Dictaphone will never be the same after an hour in close proximity to his exclamations and huge repertoire of quirky sound effects, which fulfil a vital function in propping up his vibrant but sometimes restricted English. But when I meet him at the Royal Opera House during rehearsals for his second Covent Garden run as Hoffmann, opening on Tuesday, he is troubled. “The story of Hoffmann should tell something that goes beyond just a good night at the opera,” he says, eyebrows twitching. “It’s beyond aesthetic impression, beyond entertainment.”

In part this is Villazón’s deeply ingrained commitment to the drama. I ask him about singing the title role in Don Carlo, a punishing role that he took on in May at Covent Garden to very mixed reviews, and if he’s defensive it’s only because he felt he missed out on the dramatic rather than the vocal demands. “I think there was one performance when I had an allergy, which was frustrating for me, not because I was not able to sing the notes, but because I was not able to portray the character.”

But Villazón’s passionate belief in opera “beyond aesthetic impression” goes farther than just histrionics. Last year Villazón almost walked away from his entire career, taking five months off from opera entirely. It was an audacious move, made all the more mysterious because his record label, Deutsche Grammophon, and management kept so quiet about it. It also opened up a huge debate about the 24/7 pressures facing the 21st-cen-tury opera singer.

So, what happened? “I was exhausted! And it was not necessarily vocal cords. My iron levels were low, I was in pain every week. I was trying to be close to my family, but at the same time giving interviews, promoting CDs, and recording, rehearsing and learning roles – it’s too much. It’s very hard to control your career. It’s a psychological goal you have to reach, to be happy not doing all the new productions, and all the wonderful concerts, that it’s actually fine to say no to most of them.”

He insists the break wasn’t to do with any great defects in his voice: more likely, in fact, that it was the inevitable result of the intensity with which he takes on every project, be it a CD (his most recent release, the passionate but patchy Cielo e Mar, is a good example) or a staged opera. “I always knew that with my way of being there was going to be a moment of pain. I just never thought it was going to happen so soon.”

And yet what began as a simple rest cure has taken on deeper implications. Villazón, who when we meet is clutching a a dog-eared copy of Tolstoy’s What is Art?, wants opera, and his place in it, to change fundamentally. “When I stopped I could have stopped for five weeks. I stopped for half a year. I needed to think: why do I do this? Is it for vanity? Is it just for entertainment? No. We need to look for that message that lies in every real artwork.”

It’s a war Villazón is now actively waging, albeit a tad erratically. When he launched Cielo et Mar in the UK, at a lunchtime reception at the Royal Opera House, he insisted on treating his corporate hosts to a speech in which he railed against consumerism. He sings the same tune now, castigating not just himself, but the record industry, the public and the media for trivialising the art-form. “I think the art of singing has become like a sports event with all the celebrity around it. If the hype around opera singers is not sustained by real work and by real talent, it goes away. Fame used to be associated with respect.”

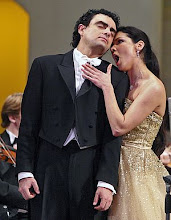

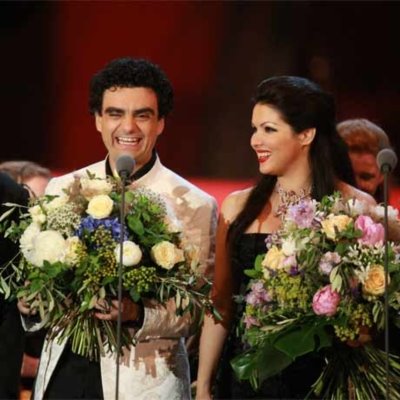

At no point does Villazón warm more to this theme, a colourful Jeremiad about the health of the Western world, than when I touch upon his much-discussed partnership with Anna Netrebko. The two prize assets of Deutsche Grammophon were aggressively marketed by the label as a duo, particularly in Germany and Austria, and until recently they sang together frequently on stage.

They also appear this Christmas in a glossy film adaptation of Puccini’s La Bohème. “A story was told through pictures about me and Anna that was not true or correct,” Villazón recently commented, an observation he now struggles to retract. “It was abused . . .” he concurs, before pausing, perhaps to consider what his label bosses might make of his words. “I think the CD label was just taking what journalism had done already – the ‘dream couple’, the ‘ traumpaar’ – and the whole thing that happened was born in the press. It sustained a couple of projects and then we go to perform with other artists. The danger is to make it all about that. But that’s the problem of our time. Fame obscures.”

I wonder just how much Villazón can really achieve of his twin goals: personal-professional balance, a recording career without the celebrity fluff. He talks of reducing commitments before revealing that he has just jetted off to Berlin to sing for Daniel Barenboim, “one of the most fulfilling nights of my life”. And he admits that image and personality not only bring new converts to opera, but are also essential on stage. “It’s a struggle. You need your individuality, you need a certain arrogance. You cannot just be an empty glass.”

Most of all I wonder whether Villazón really can overcome that “way of being”, that nerve-shredding focus on finding the drama in everything he takes part in. Could he, if only for the sake of his mental well-being, simply accept that opera might just be a job? “Yes, it’s a job, but it’s not a job. It doesn’t finish when you go home. You go home thinking of your character. Your kids go to school and then in the walk from school to home I keep asking myself – what is the purpose of art? It’s a way of living, being a performer.”

Thank Mrs Villazón, a psychologist, for bearing all this angst. “She has been the rock I can hold on to. Without her I would not be here.” So thank her, too, then, for this second crack at Hoffmann.“Four years ago it was still too much about my first Hoffmann, my first Covent Garden . . . it was still too much about Rolando Villazón. Now it’s going to be about Offenbach.” Just remember that after the ovations he’ll keep wondering whether he managed it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+2.jpg)

.jpg)

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen